Know Pain. No Pain.

Know Pain. No Pain.

Last month I wrote a blog post that opened our eyes to the ‘actual’ healing process of the human body as well as some research that educated you about what is really happening with your injuries. Understanding is the first step in an effective and efficient recovery.

This month, I want to continue our journey into this subject and dig a bit deeper into the pain that is often associated with injuries; acute & chronic. When we experience pain, we immediately link the pain to the area. Lets take a common pain complaint that all of us at one time or another will experience at least once in our lifetimes; low back pain.

I have treated patients over the years that have shown me MRI’s indicating disc herniation, yet either have no pain or the pain they are experiencing is not due to the disc pathology. I have also treated patients with perfectly healthy spines with no specific mechanisms suggest why they can barely move without feeling excruciating pain. How is it possible that someone who has a herniated disc experiences no pain at all and someone with a relatively healthy history is in excruciating pain? Well, what if I told you that the pain we feel is not due to the injury in your low back, but rather how your brain perceives the messages being sent from your low back. In other words, the ‘issue is not in the tissue’.

“100% of the time, pain is a construct of the brain” - Dr. Lorimer Mosely, Clinical Neuroscientist

Now before you think this is headed down the path of ‘it’s all in your head’, hang on a second. Technically, I suppose that since your brain is in your head, it is in your head, but it not as simple as that. You can’t simply just will your pain away or think happy thoughts. It is not a question of mind over matter.

We all learned in grade school the simple connect-the dots understanding of pain.

Step 1: You touch a hot surface

Step 2: A pain signal is sent up the arm to the brain

Step 3: The brain processes information and sends a message back to withdraw the finger from the hot surface.

Step 4: Say ‘Ouch!’

No, not exactly.

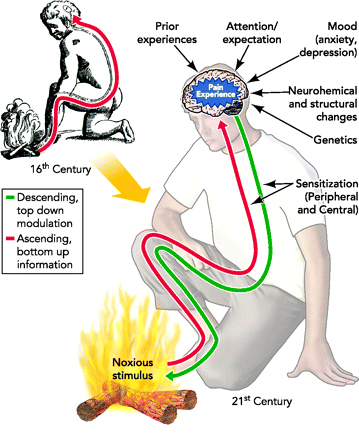

This was based on the Cartesian model of thinking proposed by the philosopher Descartes almost 450 years back. Descartes wrote, “The flame particle jumps from the fire, touches the toe, moves up the spinal cord until a little bell goes off in the brain and says, ‘ouch. It hurt’.” We have made a few tweaks to this theory over the years, yet in spite of more knowledge and understanding about pain, we are STILL not 100% clear about how to actually treat it effectively.

The human body has many different ‘receptors’ that allow us to gather information about our environment. We don’t simply have ‘pain’ receptors that tell us we are in pain. We have many different sensory sensing receptors called ‘nociceptive’ and ‘non-nociceptive’ receptors that sense temperature, pressure, and chemicals. The only difference between the two is that the nociceptors have a higher threshold than the non-nociceptors and are only activated when the stimuli is in the higher range. Contrary to what most people believe they don’t send ‘pain’ signals, they send the same signals as other non-nociceptors but just at a higher threshold.

The human body has many different ‘receptors’ that allow us to gather information about our environment. We don’t simply have ‘pain’ receptors that tell us we are in pain. We have many different sensory sensing receptors called ‘nociceptive’ and ‘non-nociceptive’ receptors that sense temperature, pressure, and chemicals. The only difference between the two is that the nociceptors have a higher threshold than the non-nociceptors and are only activated when the stimuli is in the higher range. Contrary to what most people believe they don’t send ‘pain’ signals, they send the same signals as other non-nociceptors but just at a higher threshold.

Confused yet?

In other words, there is no signal of ‘PAIN’ that goes to the brain from the body. There is only a message that is transmitted to the brain. The brain than decides what to do with this information, all in a matter of milliseconds, based upon previous experiences and several other bits of information ‘you’ have no access to. It than determines, based upon this information, what message it wants to send back to the area that just delivered the message.

At the risk of losing you at this point, I have embedded this outstanding TEDX video by one of the worlds most highly regarded clinical neuroscientists, Dr. Lorimeer Mosely. He delivers a brilliant synopsis of how we interpret pain in both a stand-up comedy style delivery without using the big words that will surely make us all feel inferior.

Take Away

I hope this post and the following video offer you some insight about how the human body ‘experiences’ pain and that it will help you to understand it better when confronted with it in the future.